Greg Distelhorst & Richard M. Locke © voxDev.org

The following text is reproduced from VoxDev.org in accordance with their Copyright and Usage policies. The original article is avalable here (source: VoxEU.org) and is reproduced in its entirety and without alteration.

"VoxDev is a platform for economists, policymakers, practitioners, donors, the private sector and others interested in development to discuss key policy issues. Expert contributors provide insightful commentary, analysis, and evidence on a wide range of policy challenges in formats that we hope are accessible to a wide audience interested in development."

For more on this research, see the American Journal of Political Science article by CIRHR professor Greg Distelhorst and Richard M. Locke (Brown University), "Does Compliance Pay? Social Standards and Firm-level Trade."

Labour standards in Asian export factories: Does compliance pay?

Compliant factories have higher quality and performance. Even so, noncompliant firms dominate the market. Could stronger financial incentives help?

Does it pay to comply with international labour standards? This is a tough question faced by many emerging market exporters. On the one hand, importers in advanced economies often ask their trading partners to observe minimum workplace standards. Yet regulators in the developing world often lack resources or simply look the other way, allowing competitors to skirt the rules. In the absence of labour law enforcement, does going beyond what the local context requires have any benefit to these firms?

Manufacturing, poverty, and workplace risks

Light manufacturing — including garment manufacturing, electronics assembly, and food processing — tends to thrive in economies with abundant labour. Their labour-intensive production processes, such as stitching and manual assembly, benefit from a large workforce with lower levels of formal education.

When barriers to trade and investment fall, these industries migrate to less-developed economies with workforces transitioning from low-productivity agricultural activity to higher-productivity industrial employment. Bangladesh and China are two of the biggest exporters of apparel by volume. Even so, lower-income Myanmar saw clothing and textile exports grow by over 600% from 2010 to 2017 (World Bank). In the blunt words of one apparel manufacturing CEO, "[o]ur industry follows poverty” (McCune 2013).

Working conditions in these factories are often vastly inferior to conditions in advanced economies. Factory work can be downright hazardous, as tragically illustrated by fatal building collapses and fires in export factories. Even when workers are protected from physical risks, managers may exploit lax labour regulation to skip paying benefits, design gruelling production schedules with no rest days, and otherwise ignore the terms of employment contracts. Indeed, the World Justice Project (2019) ranks Bangladesh and China respectively 119th and 124th of 127 countries in the protection of fundamental labour rights.

Do exporters compete on labour violations?

The risks these workers face are apparent, but the microeconomics of labour violations and exporting have been subject to debate. One school of thought suggests firms that violate minimum labour standards enjoy a competitive advantage. Complying with minimum standards can be costly — consider paying full overtime premiums rather than the base wage, a rule we often see violated in our research. International markets for apparel and other light manufactures are highly competitive. If violating certain labour standards allows exporters to offer lower-cost goods, we might expect them to seek gain by doing so.

Yet compliance with labour standards could also benefit exporting firms. Higher workplace standards may complement effective management practices that make manufacturers more productive (Bloom and Van Reenen 2006). If so, poor working conditions might undermine these practices by increasing the turnover of the most-productive workers and increasing the costs of training and recruiting their replacements.

A second possibility involves how importers – the customers of these export factories – view labour violations. Some importers may be reluctant to purchase from exporters engaged in socially irresponsible workplace practices. In the face of a scandal, these business relationships pose risks to importers’ brands and reputations. This is more than speculative, as a longstanding anti-sweatshop movement has mobilised students against harsh working conditions in the global apparel and footwear industries.

If importers fear the reputational risk of doing business with ‘sweatshops’, compliant exporters might enjoy a compliance premium where they are rewarded rather than punished for observing minimum labour standards. On the other hand, if it is indeed costly to comply with labour regulations, those cost disadvantages may outweigh any benefit.

The study: Labour compliance and firm exports

The possibility that violating labour standards offers a competitive advantage to export manufacturers speaks to longstanding concerns about a ‘race to the bottom’ in global trade. Yet it has been difficult to collect systematic data on labour violations and exports at the firm level to help adjudicate between the possibilities above. Many export manufacturers are small, privately owned establishments subject to minimal reporting requirements. Public data is therefore sparse.

To address this challenge, we partnered with a global purchasing agent to analyse its proprietary data on labour compliance and commercial transactions at export factories (Distelhorst and Locke 2018). A purchasing agent acts as a matchmaker between importers (often in advanced economies) and export enterprises (often in low- and middle-income countries). We studied labour compliance grades generated through internal audits and trade in light manufactures in over two thousand factories across 36 countries, primarily in emerging markets in Asia.

The findings

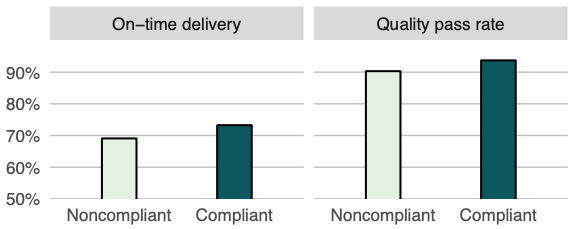

Operational performance

We first examined the joint distribution of labour violations and performance indicators collected by the purchasing agent. Factories that complied with basic standards exhibited higher product quality and on-time delivery performance than factories that failed to comply. This pattern is consistent with the idea that labour compliance is complementary to high-performance management practices that support better operational outcomes.

Order placement

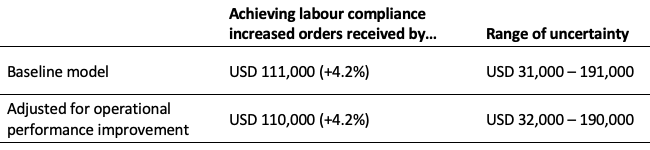

We then estimated the business impact of achieving compliance, examining within-factory changes in labour compliance over the four years of data in our sample. Contrary to the ‘race to the bottom’ hypothesis, we find that achieving compliance is associated with increased order placement. Factories that moved into compliance gained approximately 4% in annual order value on average, the equivalent of $111,000 in additional business.

This pattern was consistent across over each of the four years in our study: When factories improved in compliance, their orders increased relative to factories that remained noncompliant. When factories fell out of compliance, their orders fell relative to factories that maintained their compliance status. These patterns hold after adjusting for country, industry, and prior-year orders.

Compliance premiums or operational improvement?

Because of this link between compliance and operational performance, we were concerned that perhaps the factories gaining orders had somehow upgraded their management systems, thereby simultaneously improving operational performance and labour standards. Management practices tend to change infrequently, but even so, our models controlled for annual operational performance. We still observe the compliance premium after adjusting for annual factory performance in operational metrics.

This pattern is consistent with the idea that some importers are averse to the risks of transacting with factories that exhibit labour violations. Indeed, we observe this effect primarily in the apparel industry, where activist pressures have been strongest.

Conclusion: Stronger market incentives for compliance are needed

Despite the compliance premium documented in our research, we did not find that these commercial dynamics led to widespread compliance with international labour standards. More than three-quarters of the exporters in our sample were found to be noncompliant in the final year of our study. There evidently remains a significant market for firms that fail to meet minimum standards. A market-based approach to enforcing minimum standards across entire industries may require stronger financial incentives than we observed in our research.

Editors' note: This column is part of our series on labour rights.

References

Bloom, N and J Van Reenen (2006), “Management Practices, Work-Life Balance, and Productivity: A Review of Some Recent Evidence”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 22(4): 457-482.

Distelhorst, G and R M Locke (2018), “Does Compliance Pay? Social Standards and Firm-level Trade”, American Journal of Political Science 62(3): 695–711.

McCune, M (2013), “'Our Industry Follows Poverty': Success Threatens A T-Shirt Business”, NPR Planet Money, NPR.

World Bank Data (2019), “Myanmar trade statistics”, The World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS).

World Justice Project (2019), “WJP Rule of Law Index 2019”.